Addendum on a bijection

between \(\mathbb{Q}_+\) and \(\mathbb{N}\)

After the online publication of our paper, Professor Jeffrey Shallit

pointed out to us that the bijection that appears in our paper as equation (8), we call it \(\mathfrak{m}: \mathbb{Q}_+ \to \mathbb{N} \) defined by

\[

\mathfrak{m}\mkern-2mu\Bigl( \frac{a}{b} \Bigr) = \frac{a^2 b^2}{\operatorname{rad}(b)}, \quad a, b \in \mathbb{N},

\]

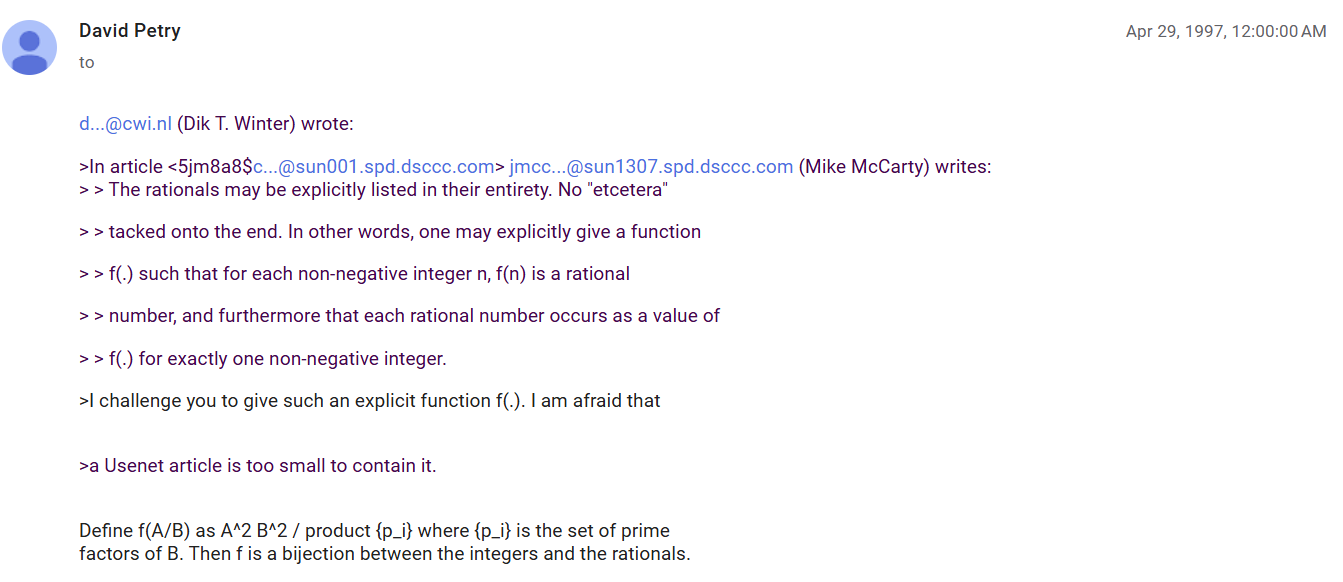

where \(\operatorname{rad}(b)\) is the product of the distinct prime factors of \(b\) (with \(\operatorname{rad}(1) = 1\)), was posted by David Petry on the

Usenet in 1997.

Here is the snippet of that post.

Although this bijection appears very simple and seems to be natural in the context that we studied in our paper,

we were not able to locate it anywhere until Professor Shallit pointed out this Usenet post in an email.

It is surprising that this $\mathfrak{m}$arvelous bijection did not receive more documented attention after being posted in 1997.

Professor Shallit also mentioned that in his paper

J. Shallit, Number theory and formal languages, in D. A. Hejhal,

J. Friedman, M. C. Gutzwiller, and A. M. Odlyzko, eds., Emerging Applications of Number Theory,

IMA Volumes in Mathematics and Its Applications, V. 109, Springer-Verlag, 1999, pp. 547–570,

in Theorem 3.6 he presented this kind of bijection that is polynomial-time computable in both directions.

As we argue in our paper, the value of the bijection posted by David Petry is that it seems to us to be "human-time" computable.

For example, in this bijection, as we write in our paper: "to find the fraction at the $90{,}316$th position requires the prime

factorization \(90316 = 2^2\cdot 67\cdot 337\); then we calculate that it is \(2/ (67\cdot 337) = 2/22579\).

In fact, given the list of all 168 primes which are smaller than 1000 and a lazy Sunday afternoon, a student could calculate the

first 1000 fractions in our bijection with a little help from an old-fashioned calculator."

We do not pretend that we have a rigorous definition of "human-time" computability, but here are two suggestions.

In the table below we list the first 168 primes. These are all the primes which are smaller than \(1000\). Using this table only, our reader could try to reconstruct the table that we present in the paper and work out its continuation. However, our reader's task would be significantly easier with the table of the prime factorizations of all positive integers less or equal than \(1000\) which we give below.

Below we give the table of all prime factorization of the first 1000 positive integers. Using this table our reader can proceed to construct the bijection and its inverse. We provide examples after the table.

The table below is inspired by

Trigonometric table (Wikipedia) that we used in high schools in Romania and Yugoslavia. Trigonometric (or Logarithmic) tables were widely used in schools worldwide through the 1970s, and they were gradually displaced as scientific calculators became affordable and widely permitted in classrooms, largely during the 1980s and 1990s (with substantial variation by country and school system). We designed the table, but ChatGPT created it following our instructions.

Let us calculate the value of the bijection \(\mathfrak{m}\) for

\[

\frac{1000}{637}.

\]

From the table we get the prime factorizations \(1000 = 2^3 \times 5^3\) and \(637 = 7^2 \times 13^1\). Thus the value is:

\begin{align*}

\mathfrak{m}\mkern-2mu\biggl(\frac{1000}{637}\biggr) & = \mathfrak{m}\mkern-2mu\biggl(\frac{2^3 \times 5^3}{7^2 \times 13^1}\biggr) \\

& = \frac{2^6 \times 5^6 \times 7^4 \times 13^2}{7 \times 13} \\

& = 2^6 \times 5^6 \times 7^3 \times 13^1 \\

& = 4\,459\,000\,000.

\end{align*}

The formula for the inverse \(\mathfrak{m}^{-1}\) is a little more complicated than \(\mathfrak{m}\):

\[

\mathfrak{m}^{-1}\mkern-2mu(n) = \prod_{i=1}^j p_i^{(-1)^{k_i} \lceil k_i/2 \rceil},

\]

where the ceiling \(\lceil k/2 \rceil\) equals \(k/2\) if \(k\) is even and \((k+1)/2\) when \(k\) is odd and

\[

n = \prod_{i=1}^j p_i^{k_i}

\]

is the prime factorization of \(n \in \mathbb{N}\setminus\{1\}\). Let us calculate now the value of the inverse \(\mathfrak{m}^{-1}\) at \(828 = 2^2 \times 3^2 \times 23^1\):

\begin{align*}

\mathfrak{m}^{-1}\mkern-2mu(828) & = \mathfrak{m}^{-1}\bigl( 2^2 \times 3^2 \times 23^1 \bigr) \\

& = 2^{(-1)^2(2/2)} \times 3^{(-1)^2(2/2)} \times 23^{(-1)^1 (1+1)/2} \\

& = \frac{2 \times 3}{23} \\

& = \frac{6}{23}.

\end{align*}

Final Comments:

To calculate the values of the bijection \(\mathfrak{m}\mkern-2mu: \mathbb{Q}_+ \to \mathbb{N}\) at a rational number the reader needs to know the prime factors of the denominator and the multiplication table.

To calculate the values of the bijection \(\mathfrak{m}^{-1}\mkern-3mu: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{Q}_+\) at a positive integer the reader needs to know its prime factorisation. However, there are three classes of positive integers \(n\) for which calculating \(\mathfrak{m}^{-1}\mkern-2mu(n)\) is particularly simple:

If \(n\) is a perfect square, then \(\mathfrak{m}^{-1}\mkern-2mu(n) = \sqrt{n}\). There are 31 perfect squares that are less than \(1000\).

If \(n\) is square-free, that is \(n = \operatorname{rad}(n)\), then \(\mathfrak{m}^{-1}\mkern-2mu(n) =1/n\). There are 608 square-free integers that are less than \(1000\).

If \(n\mkern-1mu \operatorname{rad}(n)\) is a perfect square, then \(\mathfrak{m}^{-1}\mkern-2mu(n) = 1/\sqrt{n\operatorname{rad}(n)}\). All square-free integers have this property. There are 99 integers with this property which are not square-free among the integers less than \(1000\).

There are 263 integers \(n \leq 1000\) that are not covered by the preceding three rules, for which calculating \(\mathfrak{m}^{-1}\mkern-2mu(n)\) requires a little more effort.